A cemetery isn’t your typical setting for a summer night’s entertainment, but Cinespia at Hollywood Forever Cemetery isn’t your typical cinema. Thousands of people flock to the cemetery when the weather warms to catch classic films under the Californian night sky against the backdrop of a historic Hollywood landmark.

Picnic on the open lawn lined with LA’s signature palm trees and listen to DJs play until sundown. Then sit back with a bottle of wine (no spirits allowed) for a surreal cinematic experience at the final resting place of some of Hollywood’s biggest stars. If you’re lucky one of Hollywood’s A-listers might even make an appearance (in the flesh, not the film). This is a BYO event, bring a blanket or chair – just make sure doesn’t surpass the 68-centimetre height limit.

region: North America

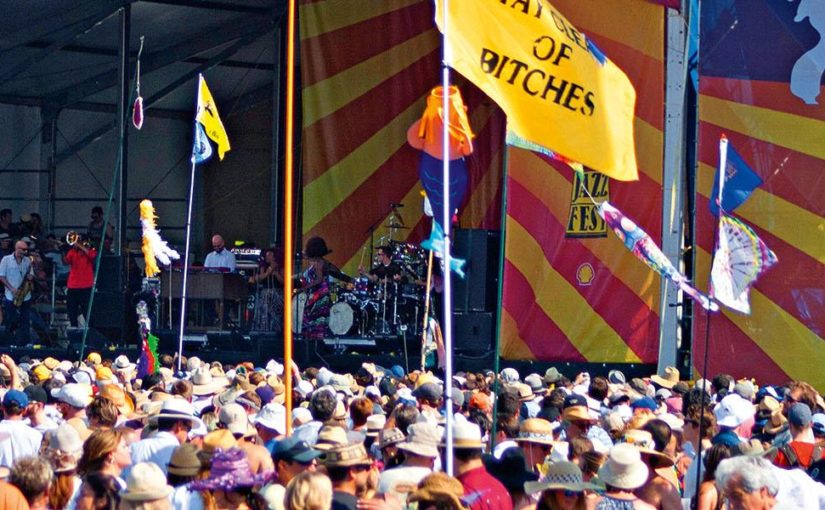

Music Festival Mothership

After a successful Friday at what might well be one of the best known music festivals in the world – where else can you see a jazz funeral and Terence Blanchard all within a couple of hours? – a very ill-advised night at the nearby Bayou Beer Garden followed. It’s fair to say that too many pints of a tasty craft beer with a surprisingly high alcohol content, a dead phone battery and a group of friends who appear to have a magical ability to disappear without trace led to new friends, even more beers and watching the sun rise over the bayou. As someone told me in the days after, as I returned to my senses, “You don’t do New Orleans, New Orleans does you.”

After battling through crowds (there are some estimates about 100,000 people were in attendance on the festival’s second Saturday, most of them beside themselves at the thought of Elton John’s end-of-day set), drinking about four gallons of strawberry lemonade and trying to find shady spots to recline, I discover a cool haven on the edge of the Fair Grounds Race Course site.

The previous day, the Gospel Tent had played host to the outstanding Irma Thomas, a powerhouse soul singer who’s been doing her thing for more than 50 years. As she sang, people rose from their seats, clapping their hands and joining in. Some ran around the perimeter of the marquee – one particular guy yelled “Hallelujah!” at regular intervals. It was certainly something to see. Today, however, it is also somewhere to sit out of the beating, hot sunshine. And there are misters sending gentle waves of coolness over everyone inside. It is, in short, an ailing person’s idea of bliss. On the stage a huge bear of a man called Pastor Marvin Sapp is singing his songs of praise. Truth be told, I’m not particularly religious – alright, I’m not religious at all – but gospel singers are storytellers of the highest order. Then, as he reaches the crescendo of a song called ‘Never Would Have Made It’, he asks the crowd to take the hand of the person beside them. Typically if you’re at a gig and a stranger grabs your hand you’d be well advised to wrest it back and bolt, but the woman next to me is beaming. “Tell the person next to you they are stronger,” the Pastor sings out. “You are stronger,” the lady trills to me in the most beautiful voice.

“Tell them they’re wiser!”

“You are wiser,” she sings. At that point, tears spring to my eyes because all I can think is, No, no I’m not. I got so drunk yesterday I can barely focus on your beautiful face. I am a moron!

As the song finishes – my singing to her is awful but received with surprising grace – I decide it is time to head out into the crowd. Drop-ins at Aaron Neville and Big Freedia almost send me to the edge, but fighting towards Jerry Lee Lewis, who’s playing immediately before Elton, finally does it – I pull the pin and head for the gates.

For music fans New Orleans itself is a dream destination. Any night of the week you can see amazing players in almost any genre performing in bars, clubs and even on street corners. Somehow though, whenever the line-up for what is really called the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival is announced, it seems to offend the purists. “Where are all the local artists?” asks one whinger on Facebook. “Not jazz,” bitches another. But this is partly the appeal of huge, well-known festivals – the money’s there to attract the big acts and therefore the crowds, but, despite what the naysayers believe, the weight of numbers at Jazz Fest truly favours local acts and the audience members who hang around at smaller stages seeking them out.

Jazz Fest runs over two weekends in April and May; Friday to Sunday on the first week and Thursday to Sunday on the second. There are 12 stages and over the course of those seven days there is a cornucopia of acts. On top of the music, there’s also amazing food, including classic Louisiana dishes like po’boys and crayfish étouffée, three different craft areas, markets and places you can find out about Louisiana’s traditions. Apart from fuelling up though, on the Friday we arrive it’s all about the music, and we approach it in a chaotic fashion, charging from stage to stage packing in as many acts as possible, while becoming increasingly distracted by frozen daiquiris and an army of colourful characters.

The bands range from bluesy rockers Johnny Sketch & the Dirty Notes and jazz saxophonist Donald Harrison to local jam band Galactic, accompanied by the ever-youthful Macy Gray, and country outlaw Shooter Jennings (yep, he’s Waylon’s son). Each afternoon, the main stages finish off with a bang. On this day the purists would have been clutching at their Mardi Gras beads as the strains of No Doubt’s ‘Just A Girl’ and Chicago smashing out ‘Hard to Say I’m Sorry’ floated over the race course.

The problem with attacking the entire program with such vigour is that, inevitably, you end up completely missing an act that’s been ‘starred’ on your Jazz Fest app. So, on Sunday, my hangover and the painful realisation that I may have missed the only opportunity I’ll ever have to see Elton John now receding memories, we plan for the long game. After studying the schedule for hours, the conclusion is drawn, particularly after the heat and crowds of the day before, to head to one of the two main stages, Acura, just after lunchtime to stake out territory and enjoy the funky ride. (There is a certain amount of hand-wringing about missing Dr John, it has to be said.)

Listen, The Meters may be better known by many as the backing band for Dr John and Robert Palmer, but they bring the funk big time. Art Neville, Leo Nocentelli and co have been slapping these beats down since the 1960s and they’ve lost none of the fire.

The excitement builds before Lenny Kravitz hits the stage. He belts out a greatest-hits set – ‘American Woman’, ‘It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over’, ‘Always On the Run’ – that gets the growing audience rocking. When he launches into ‘Are You Gonna Go My Way?’ and urges the crowd to “Jump, jump, jump” after the first chorus they obey. Just as the song seems to be coming to its epic drum solo conclusion – crushed by Cindy Blackman – Kravitz brings Trombone Shorty on to the stage. Shorty, aka Troy Anderson, is a local legend. He’s the musician who melded funk, rock, R&B and the best of traditional New Orleans jazz to come up with a sound all his own. He wields that ’bone like a weapon, reinventing the song and thrashing it for another four minutes. All too soon, it’s time for the big finale. As it has been since 2013, it’s up to Trombone Shorty and Orleans Avenue to bring it home. You can fire up iTunes or your CD player and put on a Shorty track, but nothing quite matches the electric atmosphere the guy brings to a stage. And, despite the black sunglasses hiding his eyes, he is charisma unleashed. For two hours, his trombone wails, guests like Ivan Neville and Leo Nocentelli add to the band’s already formidable sound, and the crowd dances like no one’s watching. Instrumentals alternate with vocal tracks. There’s not a person in the house, including Shorty, who wants it to end – and it goes on past the 7pm curfew with ‘Do To Me’. “My name is Trombone Shorty from the Treme. We love you, Jazz Fest! We’ll see you next year.” And that’s it. Three days after arriving, it’s all over. Luckily the Bayou Beer Garden is there to help us drown our sorrows.

Ray of Might

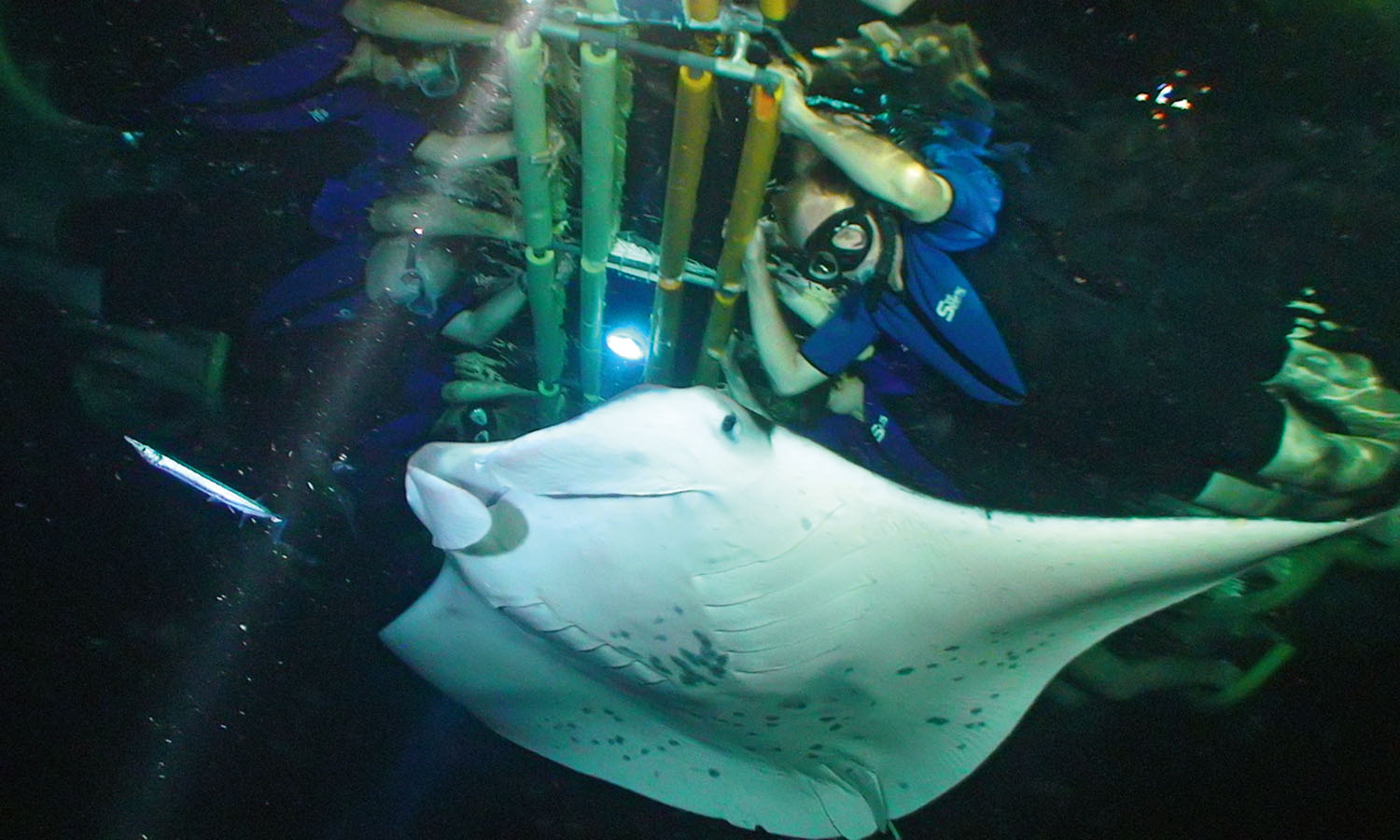

I submerge my face under the water and the romance of the moment is unexpectedly lost. There are no rays, just a bunch of slender needlefish stabbing their beaks into the dark.

Ten minutes pass. In my peripheral vision I spot the white mask of a scuba diver and am a bit miffed. He’s not with our party and is hogging our light – the very thing that attracts manta rays at night. He propels himself underneath us and suddenly I realise it’s not a mask – but two cephalic horns.

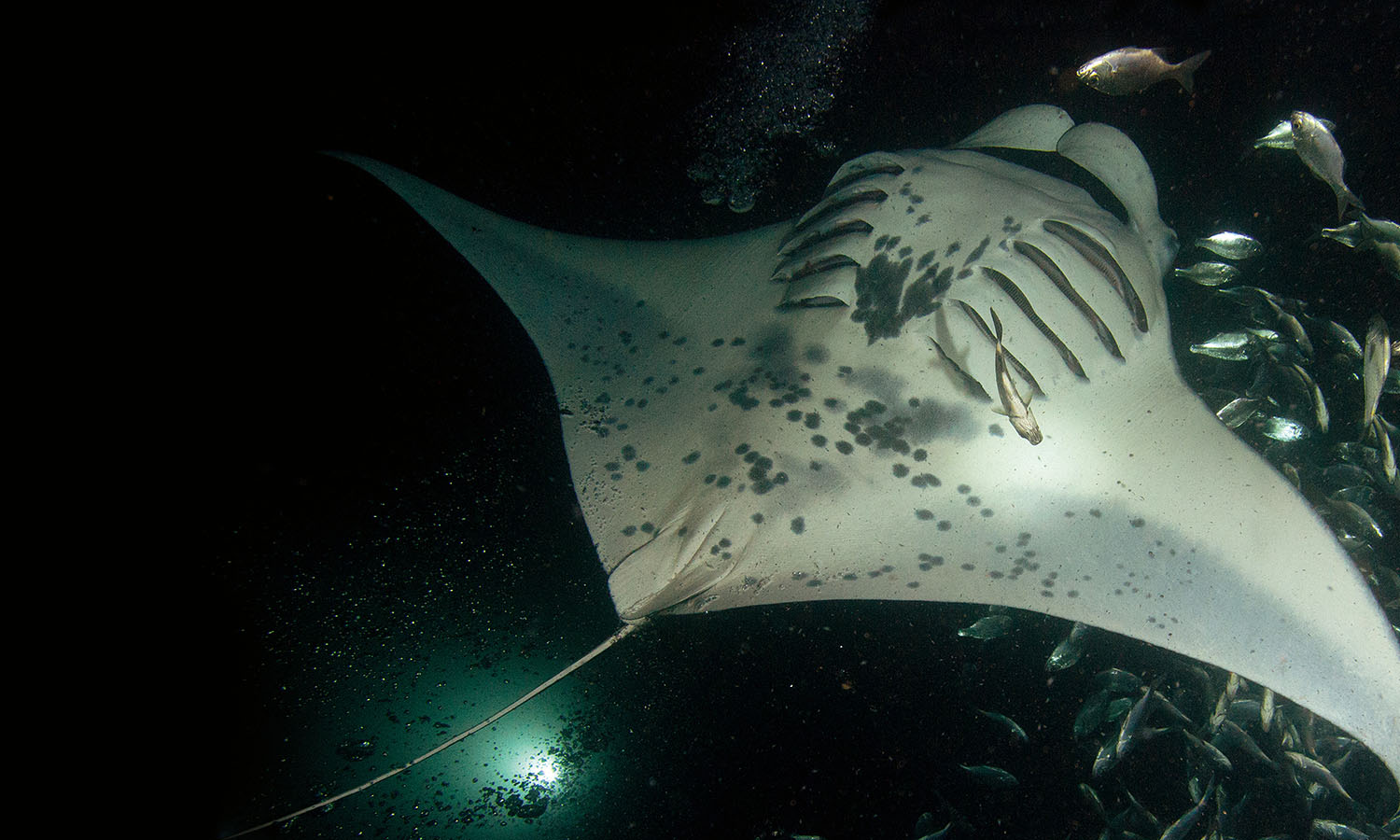

Ladies and gentleman we have our first manta ray! She’s huge – about 2.5 metres across, with a body like a toasted marshmallow: dark and speckled on top and gleaming white underneath. She circles us cautiously, like a circus animal surveying the crowd, then executes a backward roll, mouth wide open, fins graciously flapping like a giant underwater bat. Soon she is joined by two friends.

(

(