Photographer and Olympus Visionary Program member Chris Eyre-Walker captures the natural beauty of California in fine style.

region: North America

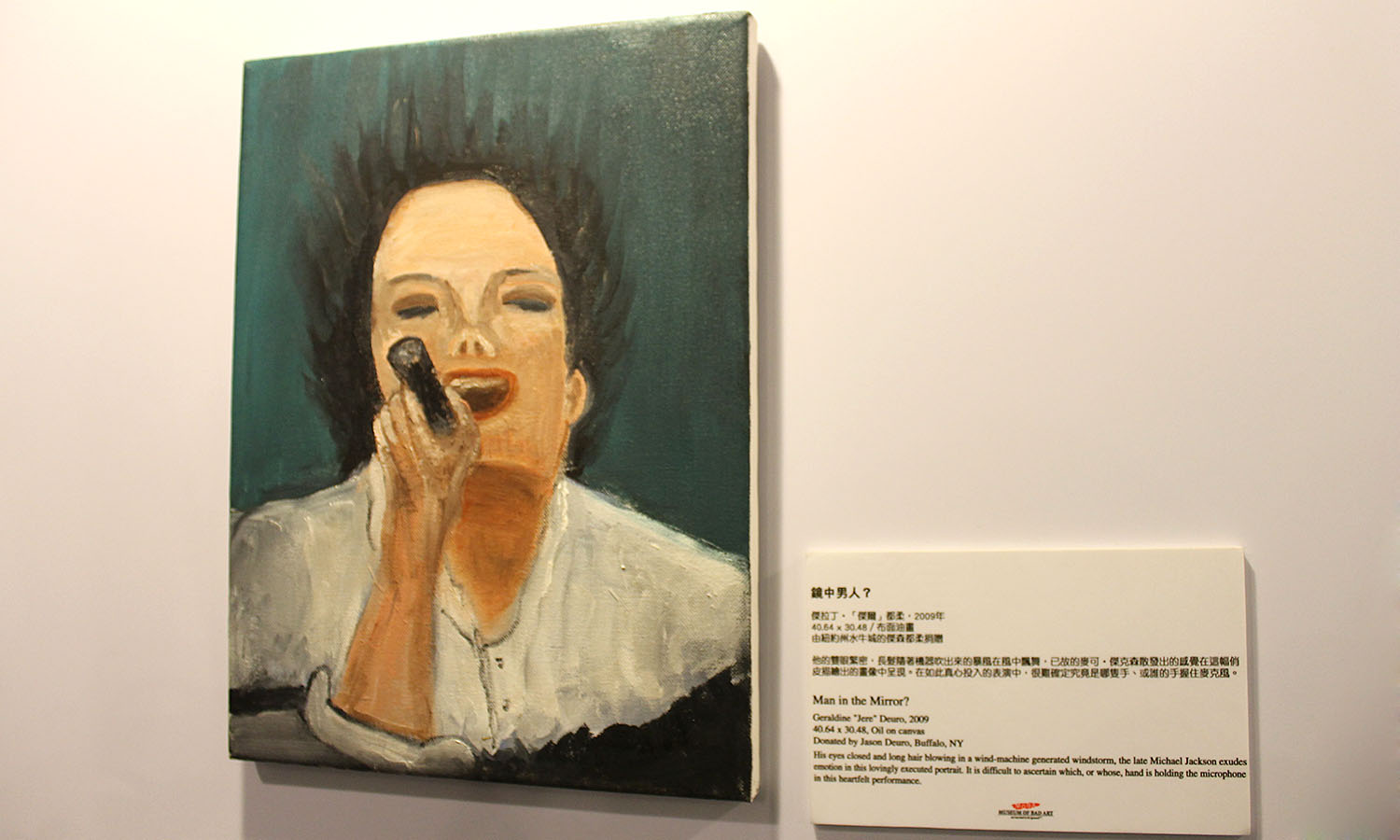

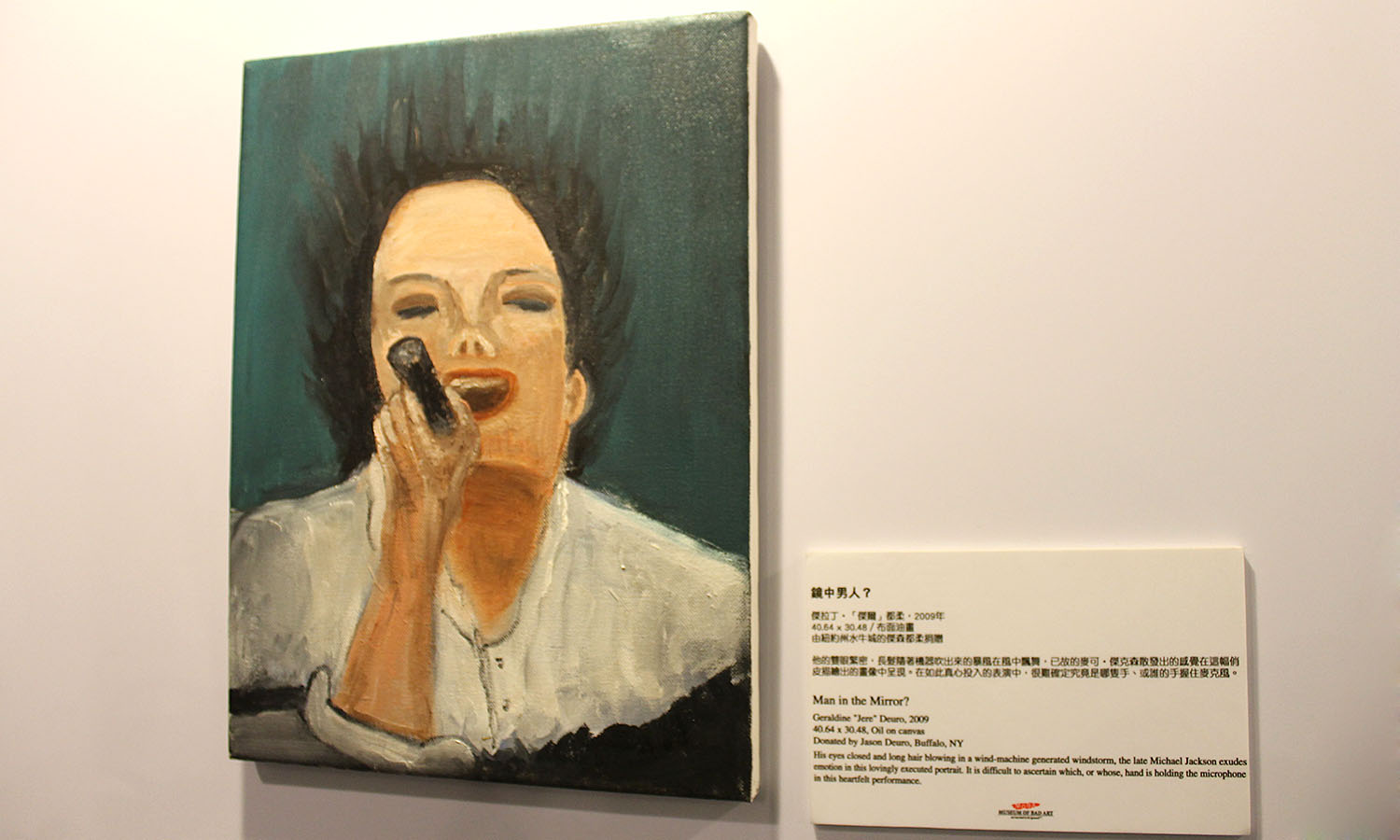

Peruse the World of Bad Art

If you’re bored with all those galleries that make you realise your creativity left you long ago, the Museum of Bad Art makes for a refreshing change. Displaying portraits that wouldn’t make your fridge door even if your progeny brought them home from kindergarten, the MOBA is exactly what it says on the tin.

Currently using the basement of the revamped 1920s Somerville Theatre as its exhibition space, this gallery shows crowd-pleasing masterpieces such as The Terrapin Pyramid and Mana Lisa.

They even go on tour, mostly around the US of A, but also overseas. For all of those tired of modernist museums full of toilets and blank canvases, MOBA is a breath of fresh air. And for those far away, the website is definitely worth browsing.

Indulge your Curiosity for Bodily Oddities

Ever wanted to inspect a three-metre-long human colon? How about the remnants of a woman whose corpse turned into adipocere, a substance that to the untrained eye looks like a melted bar of soap? If you’re feeling that dark curiosity within you stir then make sure you leave a few hours to visit the Mütter Museum next time you’re in Philly.

Originally created in 1858 for the sole purpose of research and education, the collection of odd medical specimens is now open to the public. Wander through and experience freaky abnormalities and mutations you would have never thought possible. It’s a must-see for anyone interested in the anatomically bizarre.

Boston’s Liberty Hotel

For 120 years this building housed the area’s nastiest inmates. Then, in 2007, it got a new lease on life and is now one of the city’s finest places of accommodation. Guests are warmly welcomed and escorted to their contemporary furnished rooms featuring floor-to-ceiling windows with stunning city views.

To add to the charm the architects retained some of the building’s character features, including the granite exterior, exposed brick walls, historic catwalks and striking wrought-iron chandeliers. The Liberty Hotel is the only time in your life you’ll spend a night in jail and not be in a hurry to escape the next day.

Mar Adentro

Step into the future – a world of clean lines and of white, black and blue – at Mar Adentro. With a whopping 198 rooms, the hotel is way bigger than the type of stay that usually catches our attention, but, somehow, this architectural wonder manages to make it feel as though you’ve got the place to yourself.

Its white, cubic buildings rise from a constructed lagoon, with a black-tiled infinity pool and the nest – a lounge partially sunk beneath the liquid – accessible via an inky walkway that cuts across the water. When the light is right the buildings cast reflections, giving the illusion that you’re floating somewhere in the middle. It’s all rather fitting for a place with a name that means ‘sea inside’.

In the rooms wood softens the monochrome palette and your lighting, music and curtains are all controlled with the swipe of a tablet. When you’re not lazing on your terrace or on the white sands that stretch between the hotel and the Sea of Cortez, there’s a lounge and art gallery to keep you entertained. Basically, it’s bliss.

The Cross-Country Blues

There’s a scene early in the film where the greatest-pop-star-who-ever-lived hops on a Greyhound from Atlantic City to New York (after stealing some very important Egyptian artefacts from her gangster lover who, of course, ends up dead). The bus pulls in to what seems a very glamorous Port Authority terminal at 42nd Street in Manhattan. Madonna disembarks looking better than any of us who have ever travelled on buses have ever looked. Back then, it all felt so cosmopolitan and cool. Like this was the way one should arrive into New York seeking fame and fortune.

Now, with many, many, many years of experience on a multitude of buses in varying countries, varying degrees of condition and fellow passengers in varying states of sanity, this is most definitely not the way one should arrive in the Big Apple seeking fame and fortune. For one, Port Authority is a urine-drenched, rat-infested cesspit.

But I digress. When I moved to New York from Australia in 2008, I had a grand plan to travel across this wild country on a bus. Like I was a character going through a monumental life-change in a Nora Ephron movie (famous writer/director, Gen Y-ers). It all seemed terribly romantic – and nomadic. I was wrong, and soon ditched any notion of travelling those vast expanses in a confined metal space. I discovered that people who ride buses are mainly crazy or drunk. Or both. I include myself in this group.

I remember travelling from Seattle to San Francisco. The trip, for me, was some sort of music homage: my personal ode to grunge and flower power. Or something. Ultimately, it ended up feeling like some sort of bad acid trip. A journey that should have taken 13 hours but, because of mechanical issues and other non-disclosed reasons, took 20, and comprised some 35 stops at petrol stations and diners not fit to serve anyone. The woman opposite me also cried the entire way, but refused all offers of help, save for one very bad petrol station coffee.

Then there was the time I travelled from Philadelphia to New York. A short jaunt, yes, but a trip made even briefer thanks to a maniacal bus driver who yelled and screamed at all other road users, while speeding like he had to get home for dinner. I’ve never been so happy to smell the piss at Port Authority.

My shambolic bus-riding experiences haven’t been confined to the US, though. I’ve had a few doozies in the UK and Europe as well. There are vague recollections of a journey from London to Munich for Oktoberfest with a bus full of stupendously drunk Aussies and Kiwis. Let’s just say that none of us covered ourselves in glory on that messy 24-hour ride, but we definitely covered ourselves in Fosters dregs, cheap, warm wine and, occasionally, vomit. I still feel bad for the bus driver.

I also remember a particularly harrowing five-hour (on a good day) bus ride from Manchester to London with a friend who was barely talking to me at the time. (Travelling through Europe in each other’s pockets for three months will do that.) Problem was, I had come down with a nasty bug, which left my head and, er, opposite end vying for space in a tiny bathroom with a toilet that wasn’t built to handle such a situation. I thought I could survive the five hours. I was wrong. My sulky mate sat at the front of the bus and didn’t check on me once. (Having said that, he could have been embarrassed to know me. I know I was.) To this day, I feel for all of the other passengers on that bus. I’m sure they all disembarked at Victoria Station in London with some sort of PTSD.

I haven’t felt compelled to board a bus for a long-haul trip in many a year. These days, the closest I get is stumping up six bucks to take a fancy express bus from the Bronx to Manhattan when I can’t face dealing with the unhinged people who always decide to sit next to me on the subway (that’s a whole other column). But to those same Gen Y-ers reading this, do it! Life is a highway y’all, and it’s character building. One word of advice, though… bring your own vomit bag. You’ll thank me for it later.

Whisky business at The Flatiron Room

Forget nightclubs with their blaring music, sticky floors and people packed in as tight as sardines. Set in the trendy Flatiron district, this parlour oozes sophistication and rates comfort and conversation over crowds.

Luxe booths, soft lighting and the lilting croon of a three-piece jazz band exude a vibe that’s both exclusive and laid-back, but the whisky is the true star.

Boasting more than a thousand concoctions, the Flatiron ensures everyone – from connoisseurs to first-time whisky drinkers – will feel spoilt for choice. Swill, sip and savour a glass of the smooth velvety drop or, better still, ask to have your favourite tipple put aside in the bottle keep to enjoy at your leisure. There’s no such thing as standing room here and the venue fills up fast, so be sure to make a reservation or you’ll miss out.

Sip from the tub

The term bathtub gin first appeared in the USA in the 1920s as a reference to the homemade, low-quality hooch furtively brewed during the reign of Prohibition. Tucked away behind the facade of an inconspicuous coffee shop in the Big Apple, Bathtub Gin is an old-fashioned speakeasy with a twist.

Among oversized armchairs and fringed lampshades, the bar’s most prominent feature is the gold-plated bathtub that dominates the space with a rather literal interpretation of its name. Wait staff don vintage flapper attire, while barkeeps shake up high-quality cocktails – no rotgut here – paying homage to recipes from the pre-Prohibition era. If gin’s your thing there are 30 choices on the list, as well as plenty of varieties of wine and a selection of beer.

Gramercy Park Hotel

Located on Lexington Avenue – the heart of Manhattan – the Gramercy Park Hotel is the Big Apple at its best. Each of the one-of-a-kind rooms has lush drapes, custom-designed furniture, mahogany drinking cabinets, velvet upholstered beds and walls showcasing the work of world-famous photojournalists. If you can’t get enough, keep your eyes peeled in the public area, where the ever-changing collection features the work of Andy Warhol, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

There’s a stunning rooftop terrace that features views of the city that never sleeps, but one of the main reasons to check in is your access to a special slice of Manhattan. Guests have access to the keys to Gramercy Park, one of only two private gardens in all of New York (the other is in Queens). If you want to go all out, check in to the penthouse – it comes with its own kitchen, dining room and library.

El Cosmico

Break the shackles of modern civilisation and return to a nomadic state of bliss beneath the wide, open Texas sky at this off-beat camping site. Located in the high plains desert just outside of arts hub Marfa, El Cosmico is the perfect place to unplug, recharge, do something amazing or nothing at all.

The Ritz this ain’t – choose between a gorgeous vintage trailer, magnificent Mongolian yurt, Sioux-style teepee or safari tent, each decked out in style.

Begin your day at the outdoor bath house, share a meal with your fellow nomads at the alfresco communal kitchen, explore the incredible Donald Judd and Chinati Foundation art sites, settle in for an afternoon snooze in the hammock grove, and end your evening by soaking in a wood-fired hot tub under a clear, starry sky.

(

(