An ever-changing bank of dunes hems this empty stretch of pale sand. Drive five hours south from Muscat along the Omani coastline and you’ll find one of the Middle East’s best beaches. Just back from the lapping waves, a luxury camp operated by Hud Hud Travels is the perfect romantic getaway. Amble straight from your tent into the Indian Ocean and soak away the sultry heat of Oman’s south. Here, flamingos wade with pink legs into gentle waves and eagles swoop on the surface, rising with fish glistening in their talons. During the day jump in a 4WD and take the ferry to nearby Masirah Island, where sea turtles breed, or head to Barr al Hickman, a saltpan where migratory birds flock. Otherwise just enjoy the seclusion on the sand or snorkel off the shore.

region: Middle East

Muscat’s best shawarma

Omanis go gaga for shawarma (kebabs). Every local swears by their favourite shop, but those in the know make a beeline for Istanboly Coffee Shop when they’re after a late-night snack.

Pull up a chair outside and watch the cook carve meat from a hulking spit, doling out goodies to workers ferrying packages between the kitchen and cars. Go for a wrap, packed with tender strips of chicken, and if you’re feeling brave slather on mayo laced with enough garlic to ward off vampires for years to come. Make eyes with the neon Mr Istanboly sign as you munch – he’s giving you the thumbs up for your fine selection.

Modern Omani cuisine at Ubhar Bistro

It’s easy to find hamburger joints and sandwich shops in Muscat, but Ubhar is one of the few restaurants to cook up genuine Omani cuisine. Order the muttrah paplou (seafood soup with plump wontons) coupled with ubhar harees, a porridge-like chicken dish topped with rich onion sauce, before finishing with saffron crème brûlée and frankincense ice-cream. It’s Arabia on a plate.

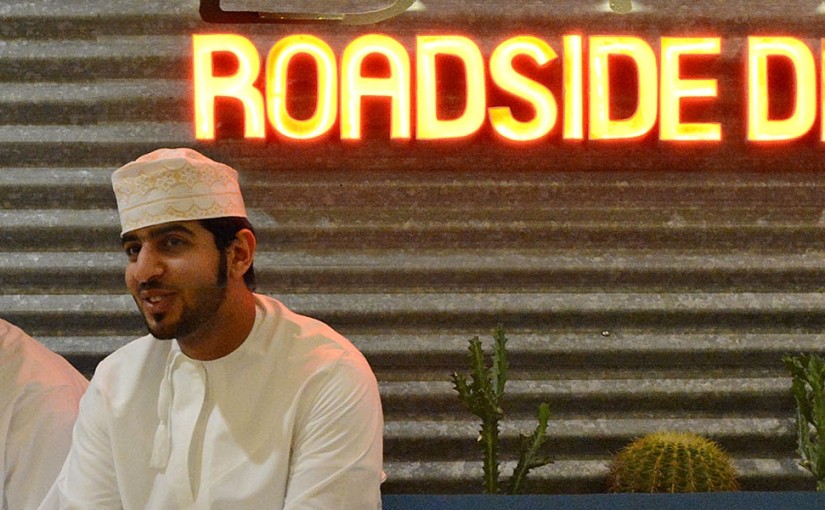

Fancy fries at B+F Roadside Diner

You’re spoilt for choice to fill your belly at Bareeq Al Shatti mall, but be sure to stop off at B+F Roadside Diner, where trendy twenty-somethings flash eyes at each other while queuing to get inside. Its signature dish of Dynamite Fries – a delicious mess of chips topped with minced beef, cheese, ranch sauce and jalapenos – is downright ugly, but boy does it taste good.

Arabian Nights at Kargeen Caffee

Fairy lights twist through trees and sweet smoke from the shisha coils beneath lanterns in the canopy at the sultry Kargeen Caffe. This is one of Muscat’s best-loved restaurants; inside its grounds you’ll find families feasting in dining rooms, men lounging in courtyards blowing flawless smoke rings and fashionistas with heels and handbags worth many months’ rent glimmering in hidden alcoves.

If you’re peckish, share a serve of shuwa, a dish of goat meat rubbed with spices, wrapped in banana leaves and roasted over hot coals for a day. But don’t get completely distracted by the food – there’s also mighty fine shisha. All the usual flavours like apple and strawberry grace the smoker’s menu, but for something more adventurous suck down a Kargeen Special, made with a selection of freshly carved fruit.

Browse Mutrah Souq by night

Tourists trawl Mutrah Souq in the heat of the day, sizing up Aladdin’s lamps and rocks of frankincense, but locals know the best time to go is at night. Stroll down the corniche, past vendors selling sweet potatoes and dates and sandwich shops with customers spilling onto the street, and enter the jostling bazaar.

If you look beyond the main passage, you can slink into a labyrinth of hole-in-the wall coffee shops, stands dripping with gold and boutiques where black-clad ladies thumb abayas (traditional robes) in fabrics of cerulean and hot pink.

Explore the Arabian Sands

Sweep between rusty red dunes and over honey-coloured peaks, then wade through lush vegetation to a freshwater oasis, surrounded by swaying palms. This is the romantic image of the desert come to life, where you can stargaze from your camp under the clear Arabian sky before mists veil the night.

You’ll encounter nomadic tribesmen who roam the sands with goats and camels, and peer down a sheer 1,000-metre drop to the bottom of Jebel Shams’s ‘Grand Canyon.’ Explore the fishing village at Ayega, once a stronghold of rebellious sheikhs, and pass a night on a dhow, a traditional sailing vessel.

Afghanistan

It’s not at the top of most travellers’ bucket lists, but the few who make the intrepid journey into this war-torn land return with extraordinary tales of amazing journeys and locals who both are surprised by and appreciative of foreign visitors.

Those who ignore the warnings from just about every foreign office in the world will no doubt land in Kabul. It’s in a rapid rebuilding phase, but there are still, surprisingly, parts of the city’s past – the Kabul Museum, the stately Babur’s Garden and the bird market, tucked away behind the Pul-e Khishti Mosque – that remain open. It goes without saying that travellers need to be take heed of security alerts and road closures.

The Bamiyan Valley, where Chinese Buddhist monks and travellers first arrived in the fifth century, is one of the most visited regions of Afghanistan. Of course, the two huge Buddhas that stood sentry at the site are gone, destroyed by the Taliban. More recently, the sixth-century statues have returned in the form of 3D illuminations onto the empty cliff. Many of the niches and grottos around the site still remain, and there are guided tours where you can see what remains of the frescoes that used to decorate them. The views from the top (where the large Buddha’s head used to reach) are spectacular.

The north of the country is vastly different. Accessed by crossing the Hindu Kush, this region is home to the magical city of Mazar-e Sharif, where it is claimed the tomb of Mohammed’s son-in-law was found, and is the starting point for treks along the remote Wakhan Corridor.

(

(