If award-winning photographer and filmmaker Patrick Trefz’s day-to-day life were to be represented through a Venn diagram, he would be the union of circles titled surf, travel and food.

Click PLAY TO WATCH

He’s somehow managed to combine all three parts of this enviable cross-section into his new book Ode to Travel, available for pre-order ahead of its actual release in February 2024.

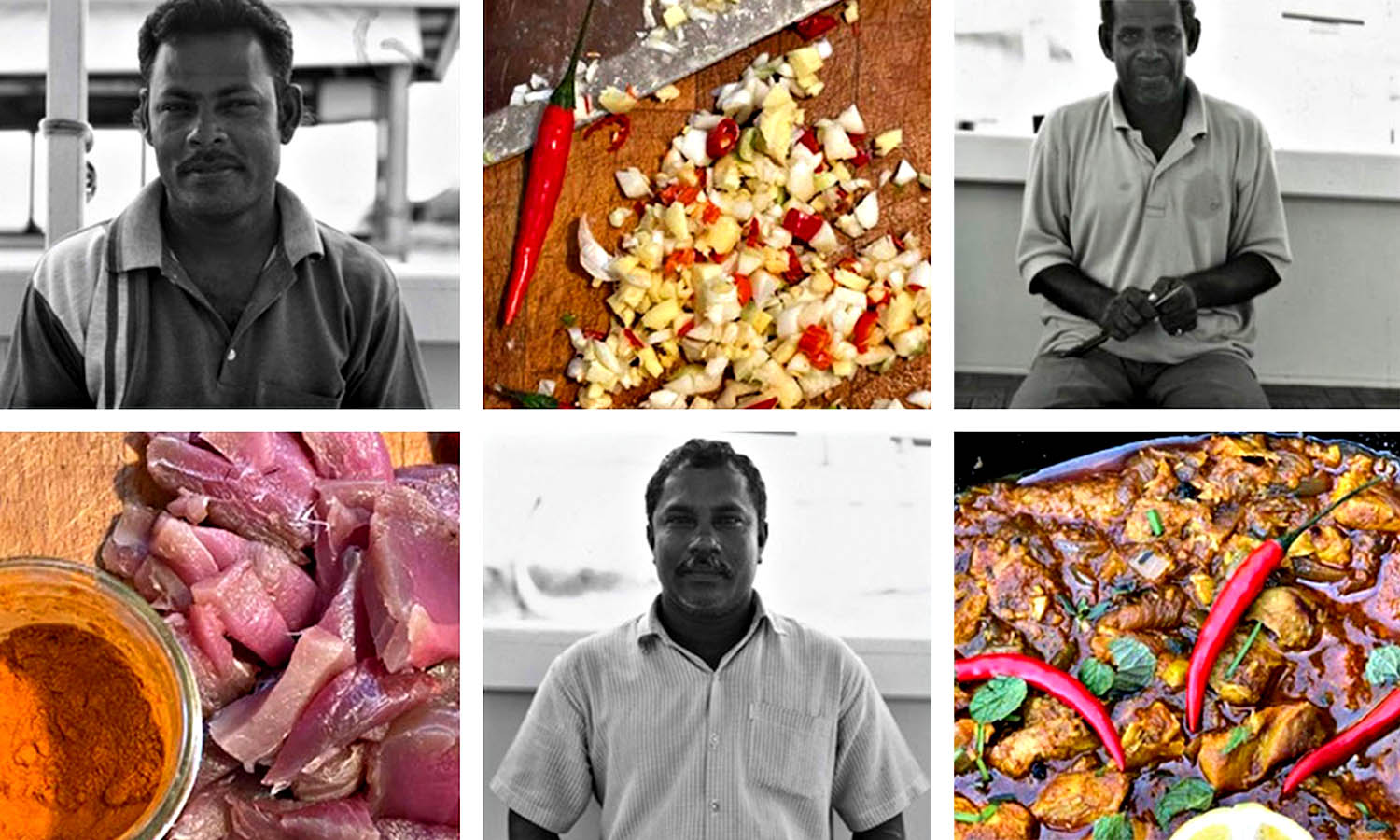

His work documenting the farm-to-table movement and championing traditions of regional cuisine is captured in Ode to Travel, which includes 35 recipes from the places Trefz has come to know intimately; each recipe representing an invitation to experience local communities through their flavours and traditions.

The 236-page, part recipe book, part travel memoir, includes contributions by land artist Jim Denevan, three-star Michelin chef and Manresa restaurateur David Kinch, and Voyage of the Cormorant author and Surfboards California owner and craftsman Christian Beamish.

We’ve scored an excerpt from Ode to Travels from Trefz’s time in the Azores, a Portuguese archipelago in the mid-Atlantic, where the surf disappointed, but the food did not.

The rugged tips of nine underwater mountains rupture the North Atlantic Ocean, two-thirds of the way from New York to Lisbon. The Açores (Azores), a volcanic archipelago, rise into a swirling mist and straddle the Eurasian, North American, and African tectonic plates.

The islands’ early inhabitants likened the ceaseless, violent volcanic eruptions that decimated their villages to the wrath of angry gods—penance for the sins they brought with them. Like the Earth’s arrhythmic heartbeat, maybe the constant ripple of tremors across the islands—27,000 within only a few months in 2022 after decades of silence—signals a cycle of destruction and rebuilding, year after year.

Ancient poets like Homer and Horace sang of the Fortunate Isles in the Western Ocean, an earthly paradise for those pure enough to enter the Elysian Fields following three reincarnations. Following Plato, the lost remains of Atlantis could have been found in the hot springs, towering peaks, and lush, fertile soils of the Açores. No people or animals populated these tiny atolls of black lava until 15th-century Portuguese explorers first docked their caravels and other small sailing vessels along the shores of Santa Maria and São Miguel—or so people say. But recent studies have unearthed evidence of agriculture and livestock up to 700 years prior to Portuguese presence—perhaps a vestige of the Vikings’ nautical abilities. When Flemish settlers arrived on the island of Faial in the late 15th century, they dried, powdered, and fermented woad, extracting a deep blue dye.

Portuguese fleets returned from India, fusing local foods with cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, and pepper. During the Spanish occupation, fleets docked in Faial’s ports, where they unloaded galleons flooded with South American gold and Caribbean spices. And in 1939, the first Boeing 314 Clipper four-engine seaplane brought Americans to Horta’s port. One late autumn, my friend Greg and I reached Horta, a port town in Faial. A city of sailors steeped in the traditions of past generations, Horta has become a quick stopover for seafarers and yachtsmen. The people of Earth’s continents converge on this tiny speck of lava-rich land in the middle of the Atlantic. We ventured away from the colourful yachts bobbing in Horta’s marina and sailed between the islands by ferry. Across the archipelago, cliffs collapse into a steep coast, vast craters bubble and boil, and boundless thickets of pastel hydrangeas line seaside roads and crown abandoned Baroque churches like the Earth sealing the scars of its past.

On a remote stretch of one of the outer islands, we searched for a place to stay the night in a small village with ivy‐covered stone houses. With no hotels in sight, a family opened their doors to us, and the father shared moonshine so potent you could run a moped on it. In the kitchen, I could smell the kale, kidney beans, and smoked chouriço sausage simmering in a pot of sopa de couve.

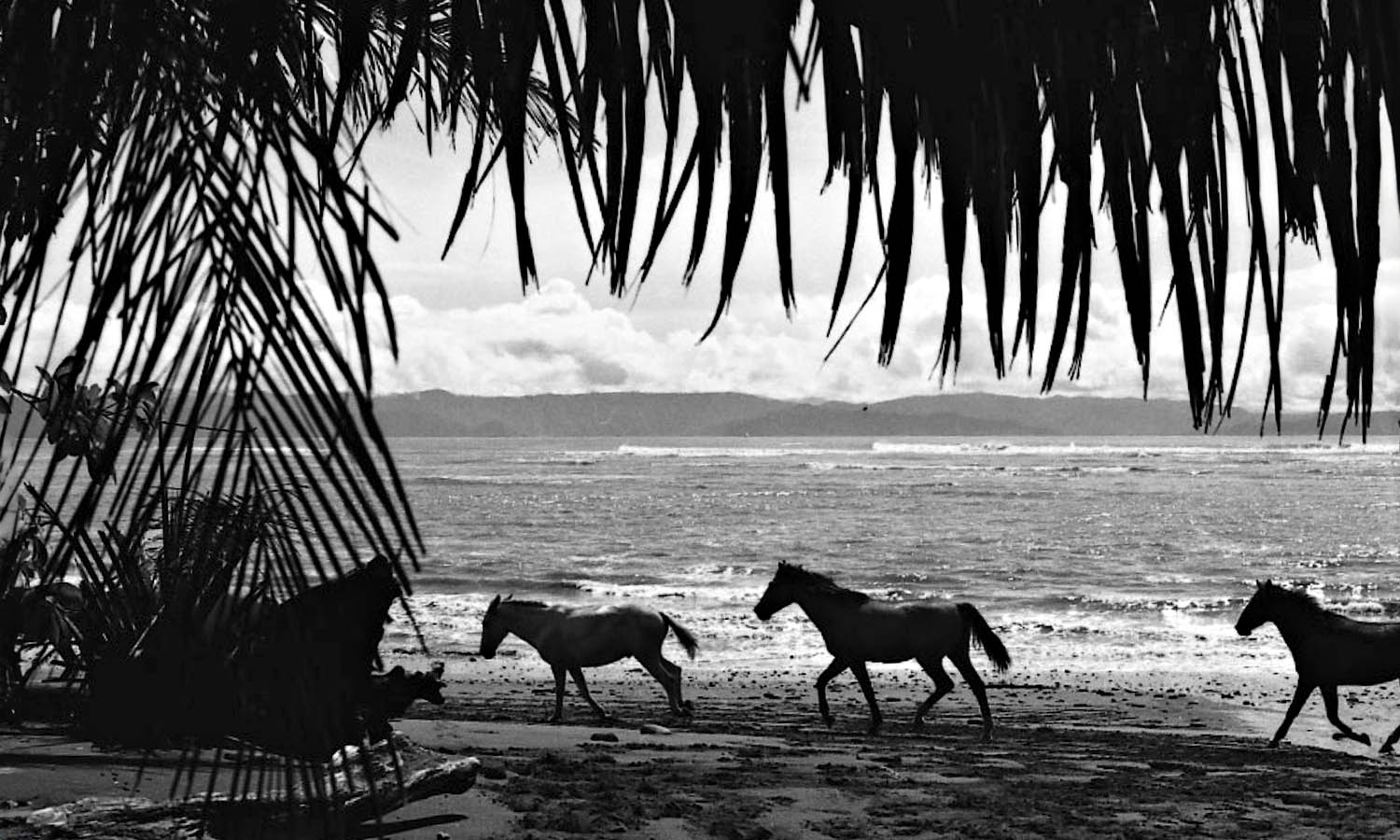

We hired a farmer in town to take us to a wave we’d spotted from way up above. Armed with rubber boots, a pack of cigarettes, and a machete, he sliced through dense brambles to unveil a forgotten goat path. Only one wrong step on this almost vertical cliff could lead to our deaths. After a couple of hours, we made it—only to find the wave blown out by the afternoon trades. The next day the swell had died and the spot was non-existent.

The sea that surrounds these islands shapes the homemade, heart-warming local cuisine. The ocean ushers in garlicky stewed octopus, grilled lapas smeared in musky olive oil, lemon, and parsley, and plates oozing with piles of pastéis de bacalhau, codfish balls made from potatoes, dried cod, onion, and parsley. Fajãs, the flat forelands formed from ancient lava, plunge into the ocean below. The fertility of these fajãs favored agriculture, and settlers once grew yams, maize, tarot, greens, garlic, and figs. Abandoned after successive waves of earthquakes, the overgrown fajãs exist as a reminder of the fleeting nature of human settlement. Pork has become a prized staple on the island.

Every Christmas, families revel in a celebration that spans several days. A pig would be slaughtered and cleaned on the first day, then hung from the ceiling as a symbol of joy and prosperity. Cows also graze in lush green pastures, and as with pigs, Azoreans waste no part of the animal. Tender tripe stewed with white beans and sausage. Chouriço à bombeiro, or the “fireman’s sausage” doused with aguardiente, a potent distilled spirit, and then set ablaze. Rissóis de carne, deep-fried turnovers stuffed with a spicy beef mixture.

We head into town, where a fish market offers eel, barnacles, limpets, and clams. And no other place in town embodies Horta’s sailing tradition like Peter’s Café Sport. For more than eight decades, this family bar has represented a cultural landmark as important as the Caldeira crater or the ruins of a church destroyed in the 1998 earthquake. A hearty dinner of Whale Soup—a beef and vegetable stew—was incomplete without Peter’s house gin. Peter’s Gin do Mar, infused with passionfruit liquor, became popular with the workers from British telegraph cable companies who made landfall in Horta more than one hundred years ago.

CLICK TO PRE-ORDER Ode To Travel

YUM RECIPE

SOPA DE COUVE

Serves 4

Kale soup has its roots in the traditional cuisine of the Azorean people, who relied heavily on agriculture and livestock for sustenance. The fertile volcanic soil of the islands allowed for the cultivation of various crops.

Kale, or couve, is a staple vegetable in the Azorean diet due to its hardiness and ability to thrive in the region’s climate. Enjoy your delicious and hearty sopa de couve from the Azores, made with kale and chorizo, a cured sausage made with pork and spices local to the Iberian Peninsula.

Ingredients

2 tablespoons olive oil

350 grams of chorizo sausage, sliced

1 large onion, chopped

2 garlic cloves, minced

2 medium potatoes, peeled and diced

4 cups chicken or vegetable broth

400 gram can diced tomatoes (alternatively, 4 to 5 fresh diced tomatoes)

1 teaspoon dried thyme

2 x 400 gram cans northern beans or other white beans

1 large bunch of kale, chopped

salt and pepper to taste

Method

Heat olive oil over medium heat in a large pot. Add the sliced chorizo and cook until brown. Then add chopped onion and garlic and sauté until the onions are translucent. Add diced potatoes and stir until they are completely coated with the oil.

Pour in broth, tomatoes, and thyme. Bring the mixture to a boil. Add the two cans of beans to the mixture and stir. Bring the pot of soup to a boil, then reduce to a simmer for about 20 minutes. Add the kale and stir in until slightly wilted and al dente. Serve warm.