When she’s happy, she asks me to pick a kimono. From a vast rail, I choose a purple one. She looks at me as if to say ‘really?’, but pulls it off its hanger anyway. For some reason, I thought dressing as a geisha would simply involve slipping a beautiful silk gown over my head. Wrong. First Tomomi straps down my chest. “You have good body, but flatter is better,” she says in halting English. Then she and her assistant Miho begin strapping and binding with sashes, belts and velcro until I can barely breathe. Finally, she walks me towards the mirror and in it I see someone who could not be me. Could it?

Tomomi runs a business called Cocomo, where she adorns ordinary citizens in traditional costume. On her walls there are photos of made-over celebs including Jessica Simpson, Taylor Swift and Betsey Johnson; in her brag book are images of tiny children in beautiful silks, men kitted out as kabuki actors or samurai, and couples posing in traditional garb on their wedding day. The preparation takes about 90 minutes before she takes me to a studio where I pose with parasol and samisen (a Japanese guitar) before heading into the street where I become the tourist attraction.

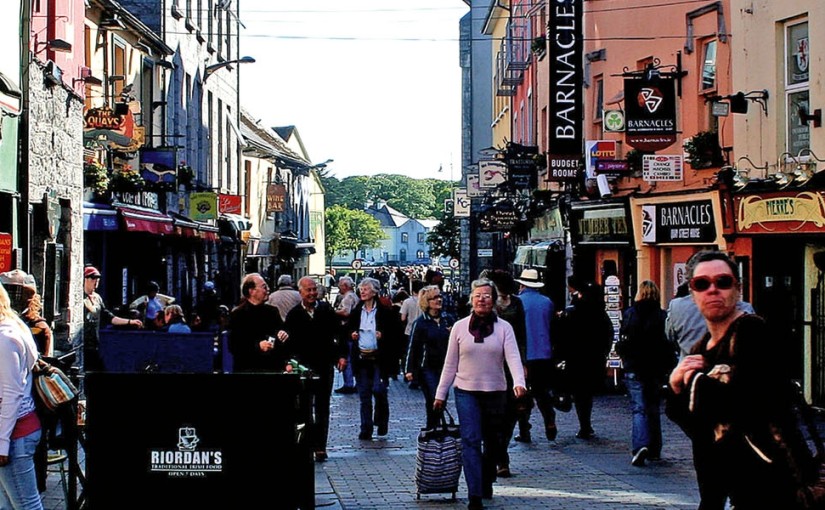

To say Tokyo is a multifaceted character is a complete understatement. Its public persona is of tea houses, tipsy salarymen, Shibuya intersection shuffling with a cast of thousands, and serene gardens dotted by koi ponds. It is all that and much more too, and if you dig a little deeper you can leave Western tourists snapping pics of kooky kids on Takeshita Street behind and explore another side of the Japanese capital. With just three days to pack it all in though, there’s just a question of when there’ll be time to sleep.

My first stop is Ikebukuro Life Safety Learning Center. Most people call it the Earthquake Museum, but that is a bit of a misnomer. Run by the Tokyo Fire Department, it deals in serious stuff. I’m in a group with a bunch of kids from the Junior Fire Brigade. Average age: 10. First we’re scared stupid by a video that shows skyscrapers swaying ominously, along with the 2011 tsunami ripping through the Japanese countryside and its devastating after effects. Next it’s off to the earthquake simulator, the facility’s newest addition. Basically, you sit around a table on a huge metal plate and it starts to shake, at which point you dive under the table and hold on tight to a leg. The instructor turns the machine up to match the 2011 earthquake, the table moves across the floor and I lose my balance and smack my head on its edge. The rocking and rolling seems to go on forever. When the shaking finally subsides my heart is pounding and I’m completely terrified. Next, the kids and I manage to escape unscathed from a burning building then douse a kitchen fire with extinguishers.

The Japanese certainly seem to have a penchant for vaguely odd museums. If you’ve got the stomach for it, the Meguro Parasitological Museum is worth a visit just for its prize display – an 8.8-metre–long tapeworm. All the signage is in Japanese, which is a little disappointing because I really wanted to know where Tapey lived before finding himself in a giant jar. It takes a couple of photos and a bit of post-visit Googling to work out what the drawings of men carrying their enormously engorged scrotes in slings are all about. Apparently Wuchereria bancrofti is a roundworm spread by mosquitoes that can cause fever, chills, skin infections and, in blokes, orchitis, an extreme and painful inflammation of the testes. If you haven’t made enough ball jokes by about now, head across the street to Ganko Dako, a street stall selling takoyaki, or fried octopus balls. Smothered in mayonnaise and bonito flakes, they’re morsels of absolute goodness.

Food is serious business in Tokyo. There are more restaurants with three Michelin stars here than anywhere else in the world (15 in comparison to Paris’s 10), but you certainly don’t have to spend a fortune to enjoy something a little different. The fish served at Zauo, for instance, is definitely fresh. That’s because you have to catch it yourself. Waiters furnish guests with a rod, a tiny unbarbed hook and a pot of miniscule prawns. Most of the tables are set on a faux boat ‘sailing’ in a pond filled with sea creatures, from small sharks and snapper to lobster and shellfish. “You have the table for two and a half hours,” the waiter tells me as he seats me in the boat’s bow and hands over my equipment. Seriously, I think, how long can a quick sushi dinner take? Well, when it takes 45 minutes to snag a snapper, the answer is two and a half hours.

My shiny, slippery snapper goes off to the kitchen and comes back on a plate. Slices of sashimi are fanned over ice, and the head and frame are artfully twisted and secured with a large skewer. Slightly off-putting is the twitching of the fins as I slurp down the sashimi, a problem that is completely solved when the remains get whisked away and prepared for the second course of fried bones.

Not nearly so close to nature is Akihabara’s cult food offering. At the front of Don Quijote (a chaotic blend of costume store and $2 shop) you can buy a Black Terra hotdog from Vegas Premium Hot Dogs. “What does it taste like?” my guide Michiko asks, tucking into a reassuringly red dog in a white bun. “Mmmm, hotdog,” is my none-too-startling revelation. It seems the colour comes from tasteless, pulverised bamboo charcoal and, as I lick the mustardy remnants from my fingers, I can’t help but wonder why you’d bother.

Akihabara Electric Town was once the place you’d visit if you were in the market for a computer, camera or other piece of electronic ephemera. These days, you can still get all that, but it’s also become the beating heart of Tokyo’s otaku (geek) culture. Head to multi-level store Super Potato and buy up big on second-hand retro games. Commodore 64 components, Atari games and Donkey Kong handhelds are all there, and there’s an arcade on the fifth floor. There are vending machines on many street corners, but the ultimate mechanised mecca is Gachapon Kaikan, a store lined with toy-vending machines. Pop in 200 or 300 yen (US$2–3), turn the handle and out pops a plastic bubble with, perhaps, a manga (Japanese comic book) character or even a hamster nibbling a carrot (replica, of course) inside.

This is also the home of AKB48, a J-pop group with 89 female members who ‘work’ on a roster performing shows every day. If you thought One Direction was a big deal, check this out – in May last year, the group released a single called ‘Sayonara Crawl’ that sold 1,763,000 copies in the first week. They’ve got a shop and a cafe and their own theatre, natch.

At 11am on a weekday morning, there’s a line-up of mostly young guys outside a huge bookstore called Akiba Culture Zone. Something may have been slightly lost in translation, but it seems they’re waiting for tickets to go on sale at 4pm for a concert that evening. Not any old concert, though – the star of this one is a female hologram who performs Vocaloid songs (basically, it’s a synthesiser that produces a singing voice). The most famous Vocaloid ‘artist’ is Hatsune Miku. In 2010, her debut album Exit Tunes Presents Vocalogenesis feat. Hatsune Miku debuted at number one on the Japanese charts and last year ‘she’ performed at SonicMania alongside bands like The Stone Roses and Pet Shop Boys.

If Tokyo’s young men seem obsessed by virtual girls – you only have to venture into the dungeon that is Mandarake, a huge store selling toys, comics and DVDs, and see them furtively flicking through manga featuring comic girls with pneumatic tatas on the covers to know it’s true – the beautiful young women of the city seem to still be searching for actual love. With real human beings. Tokyo Daijingu is a stunning Shinto shrine thought to help with togetherness. On a Saturday afternoon, a bride dressed in a glorious cream silk kimono is marrying her beau and seemingly hundreds of young women are admiring her as she has her portrait taken. They’re also buying love charms and fortunes (called o-mikuji) from priests – male and female – dressed in pristine white robes. I hand over 200 yen (US$2), shake a numbered stick from a wooden box and a priest hands me the accompanying fortune. “It’s good,” says Michiko, as she begins translating. “It says you should let the person you love go because he is too good for you. Your perfect match is a Scorpio, has AB blood and was born in the Year of the Horse. It also says it’s not time for you to get married yet. You need to be patient.” Since I’m on the wrong side of 40 and wouldn’t even know what type of blood runs through my veins, I’m wondering what she’d consider a bad fortune. These, should you be unfortunate enough to procure one, are tied to a wall, but Michiko urges me to keep mine. I slip it into my pocket along with a belled charm I hope will speed my good love vibes along.

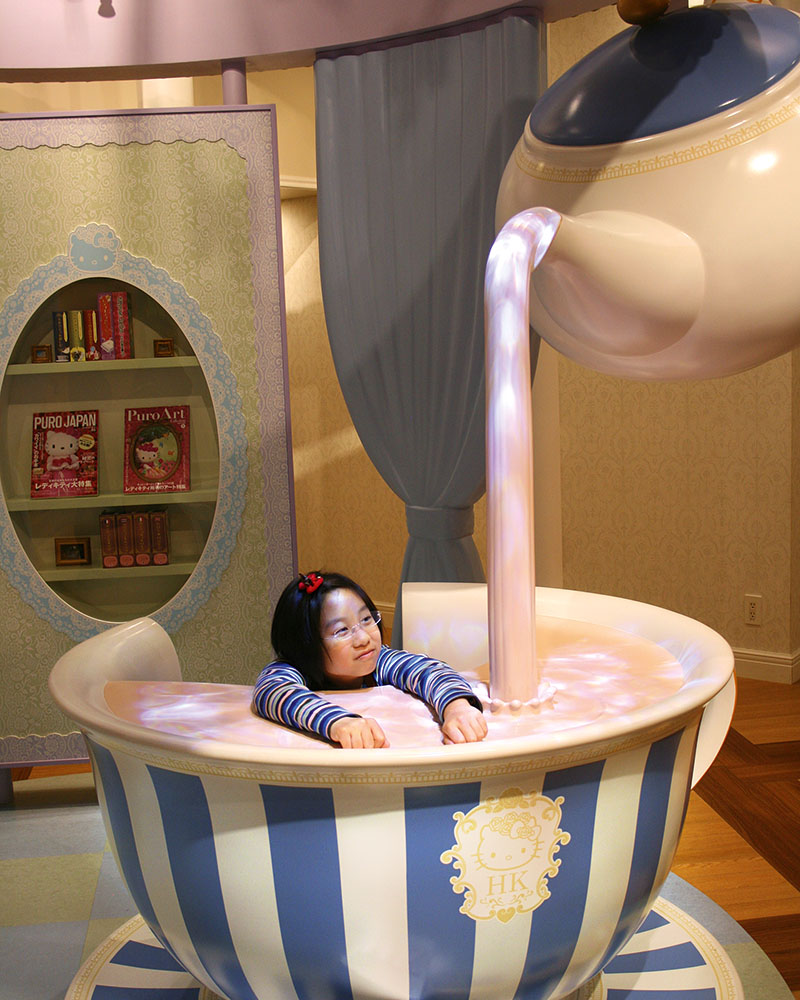

Another major attraction for young women (in many cases, the very young) is Sanrio Puroland, an indoor theme park where you can say “Hello Kitty” to Kitty. Kawaii is the Japanese word for cute and a whole industry – from maid cafes, where the waitresses sing songs of love as they serve your food, to strange police mascots with green hair and dog ears – has grown around it. But Puroland is kawaii on steroids. There are boat rides, a journey with Kiki and Lala, Kitty’s quite amazing house and shows featuring the characters that make up her extended family. That’s not to say there isn’t a sly wink to adults who find themselves here. In a musical based on Alice in Wonderland, the Queen of Hearts has her botulism-infused magic tiara stolen, instantly rendering her an old hag. In the enormous gift shop I buy a pair of socks bearing the words ‘I Love Mushrooms’ and an image of Kitty sitting on and eating mushrooms, and a face cloth of My Melody in a ghost costume printed with the words ‘Meet me in the freaky forest’. I will leave you to make your own interpretations of both.

All the outward shininess and focus on the cute does tend to hide the fact that Tokyo has a long, dark history. American researcher Lilly Fields has lived in the city for 30 years and, fascinated by its past, has a sideline in Haunted Tokyo Tours. Far from the gimmicky, after-dark schlock fests you sometimes encounter, Field’s walking tours are mostly held in broad daylight, which doesn’t make her stories any less horrifying. Her Blood of Samurai tour is the final stop on my whirlwind itinerary. We walk to the top of a burial mound, and visit a site where, in 1623, 50 Christians, mainly Jesuit priests, were crucified and burned. The methods used to torture them make the Romans seem almost mild by comparison. Then there’s the story of the 47 ronin, who avenged the death of their master Asano. Their 300-year-old graves in Takanawa are still visited by many who come to pray. Lilly is a master storyteller – one of those people who can bring a seemingly innocuous place and its history to life with her vivid words. She takes us up Ghost Hill, where we stop at a temple to visit the magical lipstick Buddha. “One of the ways to pay devotion to this Buddha is to apply make-up to it,” she explains. “Geisha would come here to pray for beauty.” There are pots of baby powder arranged around the Buddha and she encourages us to add our own daubs. I think of the love charm in my pocket and grab a powder puff. Well, you never know your luck, particularly in this big city.

(

(