When I moved to Morocco my mission was to gorge on couscous, befriend a camel and maybe learn something interesting. Armed with that impressively vague itinerary, I spent my days wandering around Rabat’s winding, walled medina, zigzagging past donkey-led carts, rows of fake Adidas tracksuits and pyramids of fiery orange, scarlet and golden spices.

In my chaotic new home, I did learn a few useful things. I became adept at ignoring street harassers slinging nonsensical catcalls, like “you smile like ice cream!” and “I love you, Britney Spears! Sex! Ha ha ha!” I mastered the precarious art of the Turkish toilet while crippled with food poisoning and I even learned how to navigate – however grudgingly – a culture where women are not encouraged to stay out past sunset.

Oh, and I also learned how to shoot a gun. Although I’m American, I’ve always been baffled by my compatriots’ gun toting, NRA-loving tendencies. I never thought I’d hold a weapon more powerful than a Swiss army knife, and in all truthfulness, I’d only ever used the scissor function on one of those things. But in Morocco, I briefly transformed into a good ol’ rifle shootin’ lady.

It happened on a trip to Oulmes, a sleepy mountain village where two classmates and I befriended Hamza, the son of the town’s most prominent family. He spoke French and even a little English, and after months of essentially miming my way through Morocco, it was thrilling.

As my friends and I inhaled the crisp scent of dirt, grass and animal faeces, Hamza sidled up with a rifle. “Shoot it,” he instructed, motioning towards the open field. And instead of asking useful questions like, “why do you have a

rifle?” or “are you going to murder me?” I took the heavy, antique weapon in my untrained grasp and unthinkingly pressed the trigger. “AHHHHHHH!” I screamed in tandem with the burst of noise and pressure, the force of the kickback causing me to topple backwards onto the ground.

Lying on the grass, half gasping, half giggling and perhaps now half deaf, I realised that we hadn’t cleared the field, and there could have easily been cows – or even people – meandering through the distant trees. Hamza handed me the empty cartridge, which I clutched in my sweaty fingers, worrying that I had inadvertently murdered an innocent bovine.

I thought my relationship with guns would end with that single deafening bang, but it was not to be. The next afternoon, Hamza piled us ladies into his 80s car, encouraged a singalong to his favourite song (Madonna’s “Like a Prayer”, naturally), and sped deeper into the countryside.

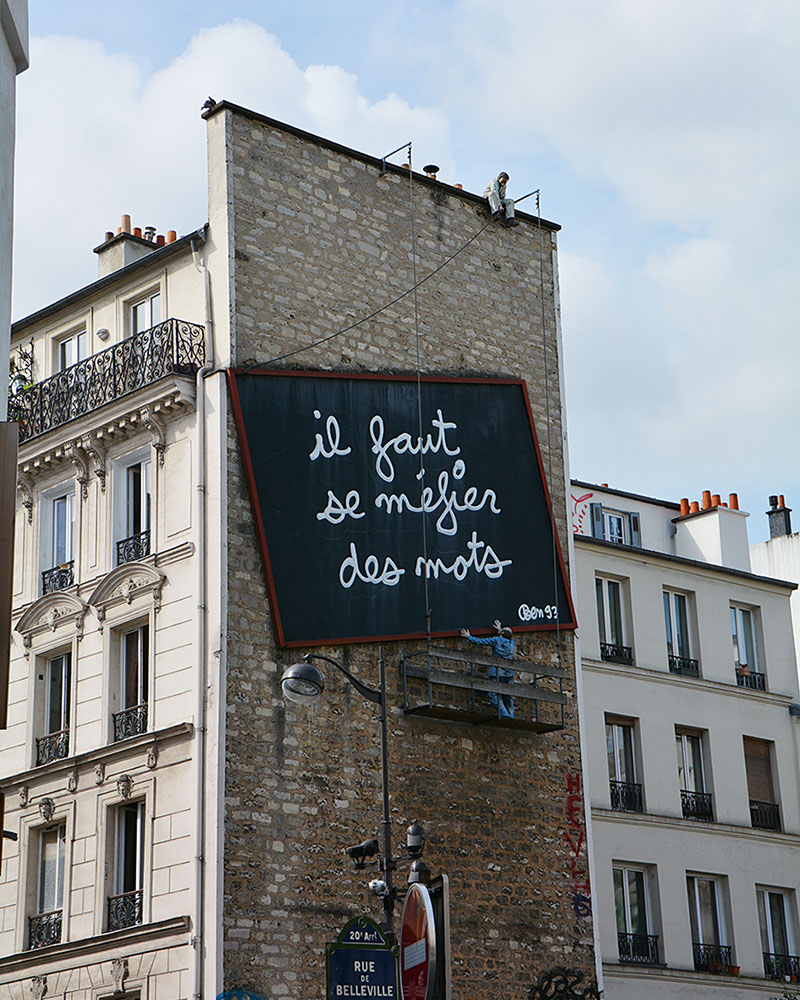

We arrived at a lab el baroud (fantasia) event, a traditional ceremony dedicated to celebrating the relationship between men and their horses. We crowded around a field, where men decked out in flowing white hats, tunics and pants galloped in unison on horses dressed in elaborately embroidered saddles and headgear. As the participants raced side by side, they simultaneously lifted their rifles and shot upwards in a collective bang that probably damaged what remained of my hearing.

Outside of the event, my friends and I shared a holy-shit-why-are-we-here moment, as hundreds of onlooking men gaped in our direction, as if we were the main attraction. Hamza led us past hordes of gawking men – who had likely never seen a gaggle of American women in their countryside before – and towards a gun shooting competition, where participants shot muskets at flying objects. As the objects catapulted into the air, contestant after contestant hit the mark, pulverising their targets.

“Let’s get you in the competition,” Hamza decided, corralling us to the front and ignoring my previously botched attempt at marksmanship.

The organisers seemed baffled that a) we were there in the first place and b) that foreign women wanted to participate, but ultimately decided that c) Hamza’s dad owned the town, so d) we were handed rifles.

It was approximately one million degrees outside (at a conservative estimate), and my matronly skirt stuck to my ankles, my long-sleeved shirt was drenched in sweat, and my hair frizzed out in a humidity halo. I glanced back at the crowd of bemused men, and at Hamza, who wore an “I Heart London” t-shirt. His elbows were certainly not covered.

Fuck the patriarchy, I thought, swiping at my damp forehead and lifting the rifle for “Lauren Mishandles Guns, Act 2”. Someone tossed a clay object in the air, and as it arched up to its zenith, I pulled the trigger.

This time I staggered backwards instead of falling (progress?), but the bullet zoomed at an awkward angle towards the ground, about as far from the target as I could have hoped. There was a collective murmur, and it went without saying that I was not invited to advance to the next round.

I did not, unfortunately, destroy the patriarchy with my wildly inaccurate bullet. But I did gorge on couscous, befriend a ceremonial horse (sadly, no camels that day) and learn a thing or two, which is all I ever wanted in the first place.

(

(